Iliotibial band Syndrome- Is it really a friction syndrome?

Iliotibial Band (ITB) syndrome is a common injury in runners resulting in lateral knee pain. Incidence of ITB syndrome can be as high as 22.2% in runners and 15% in cyclists.This pathology is also seen in weightlifters, soccer players and skiers.

Anatomically, ITB is a tight fascial structure which continues from tensor fascia lata and Gluteal maximus insertion proximally and runs along the lateral aspect of the thigh. Distally, it has multiple attachment sites such as lateral epicondyle, Gerdy tubercle, biceps femoris tendon, Vastus lateralis and the extensor mechanism. Underlying the fascia is a layer of adipose tissue which has pain sensitive Pacinian corpuscles.

Clinical Presentation

Typically, the athlete feels pain on the lateral knee and distal thigh about 2 cm proximal to the knee joint. The pain is aggravated by long training sessions, downhill running, cambered courses and attempts of increasing the stride length. Mostly the pain decreases on stopping the activity and occasionally clicking sound can be heard with the pain during the activity.

The common risk factors causing ITB syndrome include ITB tightness, increased running loads in the form of running mileage, repetitive knee flexion and extension activities, weakness in muscles around knee as knee extensors or hip especially the flexors and the abductors of the hip joint.

Is ITB syndrome really a friction syndrome?

The name ITB friction syndrome suggests that there is a shearing force between the ITB and the lateral femoral condyle. A concept of ITB friction over the lateral femoral condyle resulting in inflammation of the bursa, has been put forth by different researchers as a cause of pain in ITB syndrome. Biomechanical studies on runners show that the posterior aspect of the ITB impinges on the lateral femoral condyle. A concept of “impingement zone” is described which occurs at 30 degree of knee flexion.

Fairclough et. al. however challenged this concept of ITB friction. They not only suggested that there is rarely a bursa underlying ITB but also highlighted that ITB is not an isolated structure, but in fact, is the thickened part of fascia lata of the thigh which is connected to the linea aspera of the femur bone by an intermuscular septum and to the supracondylar region of the thigh bone by tight fibrous bands to prevent any movement of the ITB over the lateral femoral condyle. There is recent interest in a fibre complex of Kaplan fibres in relation to ITB and ACL injury.

Clinical testing for ITB Syndrome

The various tests used to diagnose ITB syndrome can be grouped into ITB flexibility tests, Strength tests and Pain provocation tests.

ITB Flexibility/Tightness test

The most commonly used test is

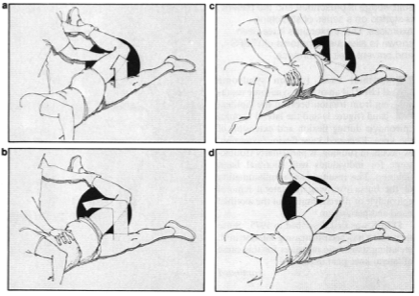

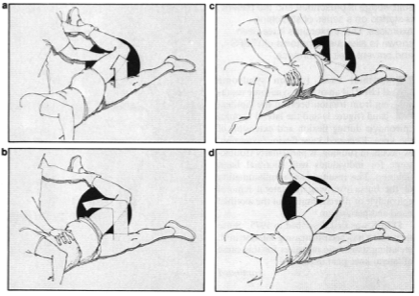

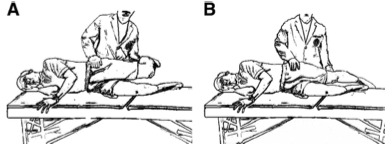

Ober’s test (Fig 1) which was described by Gose and Schweizer. Modification of this test (with the knee on the testing side is kept straight) has also been described.

Fig. 1: In Ober's test the patient lies on his side with the thigh of the unaffected leg next to the table and flexed enough to obliterate any lumbar lordosis. The affected knee is flexed to a right angle and the leg grasped tightly with one hand while the pelvis is stabilized with the other. The hip is abducted widely (a) and extended so the thigh is in line with the body to catch the iliotibial band on the greater trochanter (b). The leg is brought to the table in adduction (c). If any iliotibial band shortening is present. the hip will remain passively abducted in direct proportion to the amount of shortening (d) (Modified from (16))

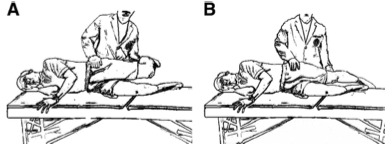

Fig. 2: A- Ober’s Test; B- Modified Ober’s Test

Strength testing

This involves testing for strength of Quadriceps, Muscles around the hip girdle. ITB syndrome is seen to be associated with weakness in strength of gluteus maximus and hip abductors, tightness of tensor fascia lata, weakness and tightness in Quadriceps along with increased lateral tracking of the patella.

Pain provocation testing

The aim of these tests is to reproduce the pain related to ITB. The tests described to elicit this pain response are the Noble’s test and the Creak test.

Noble test

The patient is examined in a supine position. The knee is flexed to 90o and the examiner presses his/her hand over the lateral femoral condyle and instructs the patient to extend the knee. As the patient extends the knee to 30o the ITB translates under the examiner’s finger. Pain at this point suggest positive test for ITB syndrome.

The Creak test

The patient is instructed to transfer his weight to the fully extended injured leg in a standing position. He is then instructed to slowly squat (one legged) to 60-90o flexion and then rise back up. Positive test for ITB syndrome is suggested by lateral knee pain along with palpation crepitus or snapping.

Investigations

Investigations such as MRI scan can help differentiate between these diagnoses if in doubt, especially for the intra-articular pathologies. MRI findings in ITB syndrome vary from a normal appearing ITB to a thickened ITB and having bursal inflammation to fluid collection underneath the ITB.

Treatment

Nonoperative treatment is considered as the first line therapy for ITB syndrome. A variety of treatment methods including modified activities and controlling the other extrinsic factors, Pain medications in the acute phase; ITB stretching and soft tissue mobilisations in the subacute phase; followed by strengthening of weak muscles in the whole kinetic chain. Specific to runners, use of orthotics to address limb length discrepancy; adding lateral wedges to decrease ITB strain; avoiding cross-training activities which involve repetitive knee flexion; and extension exercises such as swimming, hill running, track running have been suggested. Similarly, the cyclists can avoid ITB impingement by making modifications to the bike set-up in the form of lowering the saddle height, upright handlebars, progressing forward the seat position and adjusting the cleat positions.

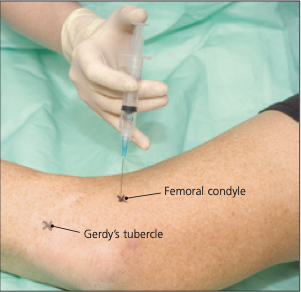

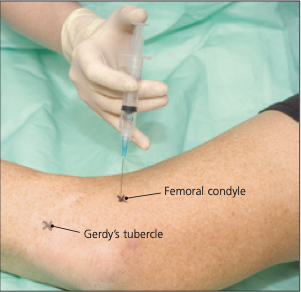

In cases not responding to these standard first-line treatments, cortisone injections have been used followed by surgical intervention in failed cases.

Modified from (9): Corticosteroid injection for iliotibial band syndrome.

Conclusion

ITB syndrome is a common overuse injury seen in the athletic population especially runners and cyclists. Identification and addressing the biomechanical factors, both proximal and distal to the knee, soft tissue tightness and muscle strength related factors along with correction of the extrinsic training loads form the first-line treatment. Surgical interventions are usually reserved for the resistant cases.

References

1. Beals C FD. A Review of Treatments for Iliotibial Band Syndrome in the Athletic Population. Journal of Sports Medicine. 2013(Article ID 367169).

2. Fredericson M, Weir A. Practical management of iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16(3):261-8.

3. Baker RL, Souza RB, Fredericson M. Iliotibial band syndrome: soft tissue and biomechanical factors in evaluation and treatment. Pm r. 2011;3(6):550-61.

4. Orchard JW, Fricker PA, Abud AT, Mason BR. Biomechanics of iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(3):375-9.

5. Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, Lyons K, Bydder G, Phillips N, et al. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. J Anat. 2006;208(3):309-16.

6. Fredricson M WC. Iliotibial Band Syndrome in Runners. Innovations in treatment. Sports Med. 2005;35(35):451-9.

7. Fredericson M, Cookingham CL, Chaudhari AM, Dowdell BC, Oestreicher N, Sahrmann SA. Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10(3):169-75.

8. Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo BD. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(2):95-101.

9. Khaund R FS. Iliotibial Band Syndrome: Common Source of Knee pain. American Family Physician. 2005;71(8).

10. Ekman EF PT, Martin DF et al. magnetic imaging of Iliotibial band syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:851-4.

11. Drogset JO RI, Grontvedt T. Surgical Treatment of Iliotibial band friction syndrome. A retrospective study of 45 patients. Scan J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9:296-8.

12. Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, Lyons K, Bydder G, Phillips N, et al. Is iliotibial band syndrome really a friction syndrome? J Sci Med Sport. 2007;10(2):74-6; discussion 7-8.

13. Batty LM MJ, Feller JA et al. Radiological Identification of Injury to the Kaplan Fibers of the Iliotibial Band in Association With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020;48(9):2213-20.

14. Gose JC SP. Iliotibial band tightness. JOSPT. 1989;1989(10):399-407.

15. Wang Tg JM, Lin KW et al. Assessment of Stretching of the Iliotibial Tract With Ober and Modified Ober Tests: An Ultrasonographic Study. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2006;87:1407-11.

16. Noble HB HM, Porter M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Iliotibial Band Tightness in Runners. The Physician and Sportsmedicine. 1982;10(4):67-74.

17. Dubin J. Evidence based treatment for Iliotibial band Friction Syndrome. Sports therapy. 2006;Dec:1-6.

18. Muhle C, Ahn JM, Yeh L, Bergman GA, Boutin RD, Schweitzer M, et al. Iliotibial band friction syndrome: MR imaging findings in 16 patients and MR arthrographic study of six cadaveric knees. Radiology. 1999;212(1):103-10.

19. van der Worp MP, van der Horst N, de Wijer A, Backx FJ, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2012;42(11):969-92.

20. Pinshaw R, Atlas V, Noakes TD. The nature and response to therapy of 196 consecutive injuries seen at a runners' clinic. S Afr Med J. 1984;65(8):291-8.

21. Gunter P, Schwellnus MP. Local corticosteroid injection in iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38(3):269-72; discussion 72.